|

|

The Large Hadron Collider

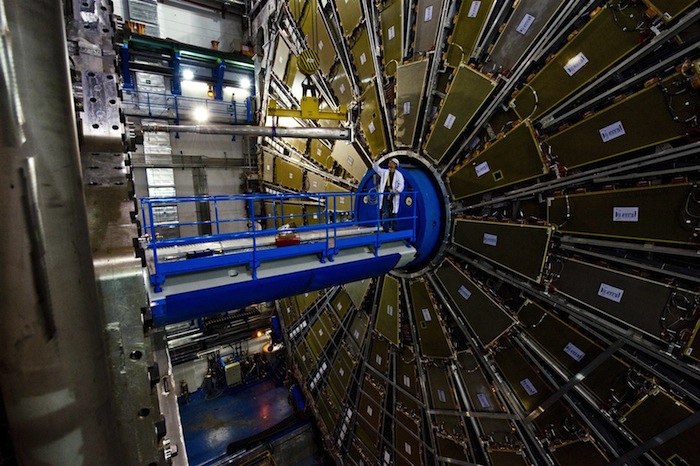

As mentioned earlier, aspects of the scores for each piece of music on this project were directly synthesized from data generated by the Large Hadron Collider. The LHC is the largest particle accelerator in existence and is arguably the most complex machine ever built. It is an astonishing testament to what we as human beings can do if we work together in a positive manner. Located on the French/Swiss border its development, construction, and subsequent use have involved the cooperation, both financially as well as technologically, of over one hundred countries. As I understand it, any physicist in the world may access the data it produces as well as conduct experiments using it either on site or remotely. The super-computing grid, that was created in order to accommodate the more than six million pieces of data that are collected in any single event, is second to none and is in itself a technological marvel. |

|

|

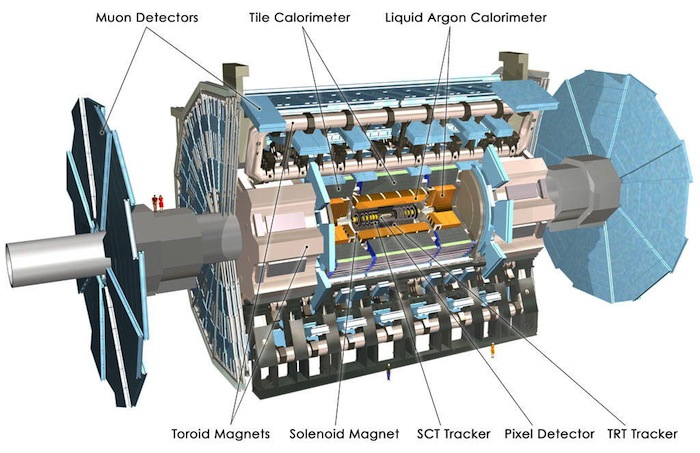

The process involved in producing Hadronized Spectra, which was completed in January of 2013, was an interesting and lengthy one requiring almost two years to accomplish. It began in the spring of 2010 when a friend mentioned that Dr. Lily Asquith, an English physicist working at the LHC, had been interviewed on NPR about a project she was spearheading called LHCSound. Though I am not a physicist, I am very interested in quantum physics and so I was quite intrigued by the idea of using the LHC data as a basis for a composition. After listening to the interview online, I immediately contacted her. Several informative emails later, I was kindly provided access to several sets of data from proton collision events collected by the Atlas detector.

It was clear from the beginning that using the data provided would present an intense challenge. The numerical representations of the proton collision events were very difficult to work with and yet adhere to my rules for sonifications and so it was at times overwhelming. Allow me to explain why by first providing a layman’s description of the process of hadronization. |

|

|

Protons are stripped off hydrogen atoms and are then accelerated to 99.9997% the speed of light by extremely powerful electromagnets. Two streams of protons, each traveling in opposite directions, are beamed within a circular underground tunnel that is almost 17 miles in circumference. At top speed they make the circuit 11,000 times per second. The streams are then crossed within a given detector such as the Atlas, there are four at the LHC, and as the protons collide measurements are taken. The heat produced by these collisions is many times hotter than the temperature at the core of the sun. As a result of the collision events “hadrons” are produced, which are quantum level sub-particles. Included in the list of sub-particles are several types of quarks and gluons. As the protons come apart in a collision, the angle at which each sub-particle splits off, the energy it releases, and many other aspects are detected and measured. Here you see a list of five of the data parameters I was provided and descriptions of them using the quantum physicist’s terminology. |

Dedicated to the Advancement of Human Consciousness